(Part of the “Self/Systems of Meaning Blog,” by Clara de Castro, Henry Hauser, and Emily Lynch)

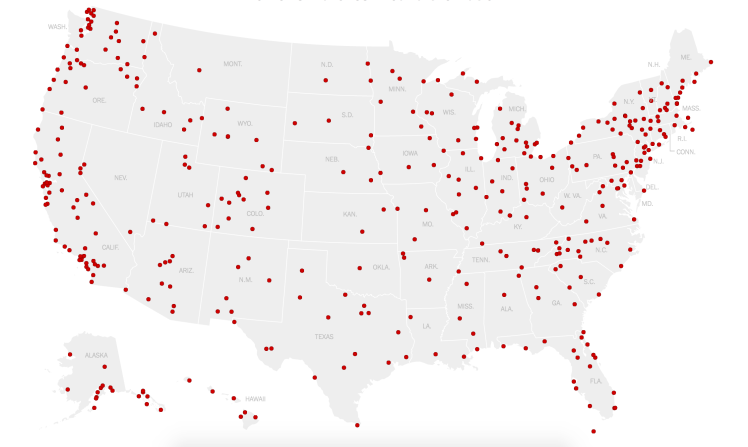

On Saturday, January 21, 2017, a massive crowd descended upon the National Mall for the Women’s March on Washington. According to crowd scientists asked by the New York Times, the event drew at least 470,000 people, more than three times as many as had attended President Trump’s inauguration the day before. And many more attended the “sister marches” taking place around the country:

As well as around the world:

All told, the global total of people taking part in these demonstrations was, according to ABC News, over one million. Among the largest of the sister marches was Chicago’s, which, according to the Chicago Tribune, drew a quarter of a million people. All three contributors to this blog were among those 250,000, and we’ve decided to make this post a collection of our three individual perspectives on our experiences of the march, and their resonance with the Durkheimian ideas we’ve been discussing in class (combined with photographs we took at the event). Because this post deals largely with our individual experiences of what it meant to be a part of the collective this Saturday (as well as our individual perceptions of how others were participating in group life), we thought it best to format the post as three individual pieces, each written by one person, rather than trying to combine the experiences of different individuals. The risk, in doing this, is to be slightly repetitive, but we believe the benefits to be greater than the risks. Please enjoy!

Henry Hauser

When I first heard of the Women’s March, I’ll admit that I wasn’t sure whether it was an event at which I would be welcome. Not because I had any reservations about supporting any of the causes for which the march stood, but because I wasn’t sure if the presence of a man at a self-described “women’s march” would be appreciated. I was worried that it wasn’t my place and that I’d be perceived as speaking on behalf of women rather than allowing them to speak for themselves. However, at yesterday’s march, I felt nothing but welcome. An examination of the symbols (or, to be Durkheimian about it, “totems”) the group used to represent itself helps explain why I felt this way

One of the clearest symbols of the group of protesters was the so-called “pussy hat” (as seen above), a bright pink knit cap with cat ears. The hats, the product of the Pussyhat Project, clearly functioned as a totem in the Durkheimian sense. It was a representation of the group as a whole. Individuals wearing the hats were immediately identifiable as members of the group of people who had come out to protest that day. And even for people not physically present at the rally, participating in rituals involved with the hats allowed them to feel like they were part of the group: according to the Pussyhat Project website, one of the projects primary missions is to “provide people who cannot physically be on the National Mall a way to represent themselves and support women’s rights” by knitting hats for those who would be present. The stated purpose of these hats was to express the idea that at the protest, the group as a whole represented something greater than any one individual: as the project’s website says, “If everyone at the march wears a pink hat, the crowd will be a sea of pink, showing that we stand together, united.”

But to me, it seemed that the pussy hat was part of a larger totemic symbol present at yesterday’s rally: that of the color pink in general. As a snapshot of Washington, D.C.’s rally shows, the color pink made its present felt at yesterdays protests:

And in Chicago, too, pink was everywhere, and not just on people’s hats. The protester two photos above carried a pink “Rise Up” sign in addition to her hat. Another protester, without an official pussy hat, wore a pink baseball cap and carried a sign written in pink:

And one of the more powerful images I witnessed yesterday was that of a father and daughter wearing matching pink bandanas in support of the Women’s March:

Outside of the hats alone, the color pink seemed to be widely, if not universally, seen as one symbol of yesterday’s protest. In fact, my own father and brother, who attended the D.C. rally, opted for the only pink articles of clothing they owned: jerseys of the Italian soccer team U.S. Città di Palermo. For those who wore pink, the color seemed to serve as a way to identify with the larger group. In other words, it represented a way for individuals to feel like they were more than simply their individual selves, but rather parts of a collective, more powerful than each individual.

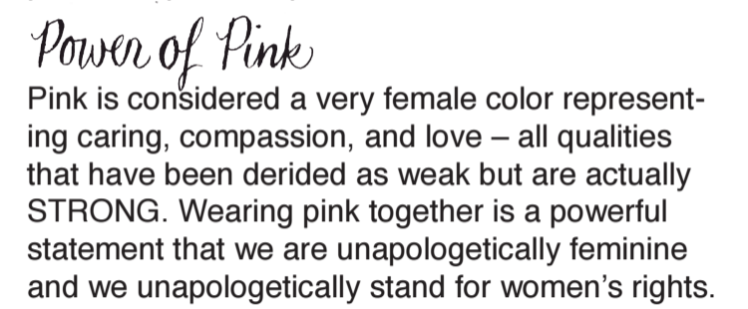

If, in fact, pink was a collective representation of a group, it is probably worth examining exactly of whom this group consisted. The Pussyhat Project website provides one perspective on pink as a symbol:

I, in general, do not love the idea that pink is the domain of just one gender, as my classmates can probably guess, if they have noticed the pink notebook, pink iPod, pink flowery phone case, or pink/zebra print backpack I usually have in class. That being said, as a way of reclaiming an often ridiculed symbol of femininity, and fighting the idea that that which is feminine is weak, it seems to me a powerful symbol. But, although pink seems to have been chosen because it is seen as a traditionally feminine color, it was not only women at the march who participated in the symbolic use of the color. For example, men such as the bandana-wearing father, above, and the male members of my family, wore the color as well. So, at the marches, participation in the collective was not defined by one’s gender. The march was not one that consisted solely of women. It was one that consisted of anyone who subscribed to the idea that women are valuable members of society whose voices are worthy of being heard and whose rights are worthy of being protected (an idea that many, including myself, would argue was challenged quite a bit this election cycle). And the presence of many other, seemingly totemic, symbols which I do not have the space to discuss at the march indicates that group membership was also defined by subscription to a number of other ideals, regarding immigration, climate change, racism, and more. Given this, even though I did not happen to be wearing any pink at the time, I felt quite welcome at the march.

My experience at the march has had me thinking the last couple of days about whether the kind of totemism Durkheim describes, in which certain symbols form a collective representation of a group, is ultimately a positive or negative force. The Pussyhat Project, of course, is not the first group of people to use hats as a collective representation. Nationalist movements, including Trump’s, have always made use of the collective effervescence their members feel in being a part of a group, as well as strong use of symbols representing these groups: the swastika, the MAGA hat, etc. And they have defined their groups by a method of exclusion: saying that being a proud German means hating your Jewish and Romani neighbors; saying that being a proud American means being suspicious of your Muslim and Mexican neighbors. But in yesterdays case, the same forces of totemic representation were at play, and seemed to me a force for good. Perhaps these are not inherently negative forces, when totems can represent groups defined bot by their hate but by their tolerance.

In closing this piece, I’d like to return to the proud Octopus tradition of exploring Durkheimian ideas through fish-related cartoons. In the sign in the photo below, the image of a school of fish is used not, as we have seen in class, to extol the virtues of individuality, but to glorify being a member of a group. In the image, a big orange fish is being swallowed by an even bigger fish, itself made up of tiny fish of many different colors. This, I believe, represents collective effervescence at its best. Being one of those small fish, I would argue, means being part of a greater force for good, when the big orange fish is Donald Trump.

Emily Lynch

“There are three major forces at play in big groups like this: collective effervescence, totems, and squish,” a fellow University of Chicago student muttered to me as we squeezed our way into the overcrowded 55 bus en route to the Chicago Women’s March. I hadn’t even mentioned that I was studying Durkheim.

Many times during my experience at the Women’s March, I was struck with unmistakable similarities between what I have read in The Elementary Forms of Religious Life and what I witnessed in front of me. I quickly realized that the march was essentially a modern-day corroboree, abounding with totems and radiating collective energy. On the surface, the event was overwhelmingly tribal: I saw five drum circles and thousands of painted faces over the course of the day. Protesters shouted chants like “Hey hey, ho ho. Donald Trump has got to go,” and “This is what democracy looks like.”

Though there was one identifiable totem, the pink knitted “pussy hat,” the march otherwise brought together a crowd of people wearing clothing and bearing signs as diverse as ever. There were certainly themes, different schools of protest attire and signage. Some protesters took a lighthearted stance, holding posters reading “We shall overcomb” or “Donald Trump uses comic sans.” Others were more earnest: “My autistic students deserve better than a president who mocks disabled people,” and “Marching for the women who had to work today.” What shocked me most, though, was the range of specific causes on display (female reproductive rights, the wage gap, LGBTQ rights, immigration reform, Black Lives Matter, and climate change, to name a few examples). Though our individual causes varied, protesters agreed that 1) we need to address many problems, and 2) we can only solve these problems collectively.

In regards to the idea of “collective effervescence,” I think I went into the event with false standards. In Durkheim’s description of the corroboree, he states that since “the very act of congregating is an exceptionally powerful stimulant,” participants feel an eternal, electric force (217). I entered the march expecting, at least hoping, to feel possessed by this force, to lose myself in the mass. Since I felt relatively sane and never engaged in “outlandish behavior,” I thought I never truly lost myself (218). But collective effervescence doesn’t need to entail outlandish behavior. An unbridled sense empowerment, feeling like you are a part of something bigger than yourself, is electric in and of itself.

I overheard a child who expressed this idea better than I can. When her father asked her how she was doing, if her feet hurt from walking so much, she replied, “If all these people are walking, I can too.”

Clara de Castro

So I went to the Women’s March downtown Chicago not really knowing what to expect. I had never been to a protest and the only march I had ever been to was a 100-person Martin Luther King march in my hometown, and it was very different from the hectic scene I was about to walk into. I went to the march alone armed with a camera. I was able to weave through the crowd taking portraits of the marchers and their signs. I could not help but chant and cheer and march down Michigan Avenue. The rhetoric was united WE stand and together WE can make a change.

Most of the time they did not have official police barriers, marchers linked arms and blocked the cars from turning onto Michigan. Just by joining in a group, the marchers were able to stop a powerful vehicle that is enormously more powerful than the individual.

The official police barricades around Trump Tower blocking the entrances from the protestors with officers on horseback. They were ready—just in case. The power of the collective had to be prepared for.

Strength was in numbers.

To apply Durkheim to the Women’s March, there seemed to be a lot of ‘totems’ present. The modern ‘totem’ seemed to be a unique cause. We were not just marching for Women. The causes included Black Lives Matter, Immigration, Climate Change, Veganism, Healthcare, unspecified Anti-Trump, Free Higher Education, Free Palestine etc. People had signs and shirts telling everyone around them what group they were a part of. We chanted, sang, and marched, however, as one collective. Durkheim describes this phenomenon as a corroboree that is when “ the individuals gathered together, a sort of electricity is generated from their closeness and quickly launches them to an extraordinary height of exaltation. Every emotion expressed resonates without interference in consciousness that are wide open to external impressions, each one echoing the others (217-218).” I felt that electricity being in the crowd. I couldn’t help myself. The religion we were marching under seems to be democracy. That is the system of meaning that brought us together regardless of our ‘sub-totemic’ cause. Everyone was welcome, even the uninitiated, to put it in Durkheim’s terms, as is with the corroboree.

Trump did not fit under the religion Democracy or the United States. If Trump is not American, then what is? What does it mean? It is obviously not literal citizenship.

The reason why the collective is protesting is that they believe that Trump does not follow the rules and restrictions and rituals and rites that makes one American.

We discussed this briefly in class that the Constitution unites us and Trump threatens to truncate those rights it grants. He is breaking the agreement. Trump does not follow principles of the Democratic and American religion – therefore he is not American.

There was no clear unifying object that was our totem. Durkheim said that we need a tangible object or symbol, “It is symbolic representations of this or that plant or animal. It is totemic emblems and symbols that possess the greatest sanctity. And so it is in totemic emblems and symbols that the religious force is to be found” (208). The obvious totemic emblem would be the American Flag. So why wasn’t everyone rallying under the flag? There were of course a few flag wavers but not a large number. How did I feel such intense collective effervescence without a flag? We needed a symbol, “without symbols, moreover, social feelings could have only an unstable existence” (232). Durkheim believes that we need to objectify the collective to be able to comprehend something that is greater than us. What was that totem for us marchers?

I started to think of what we were actually chanting: ‘This is what democracy looks like’.

Democracy is the religion and we are as a collective are the totem. The protest and the march was the totem. It is the tangible objectification of democracy. The totem is a ritual.

It is important to protest and to march to further causes one believes as well as to heed Durkheim’s warning that, “all forces, even the most spiritual, are worn away with the passage of time if nothing replenishes the energy they lose in the ordinary course of events” (342). We need to re-acknowledge the power of the totem to have stability in the collective.

I took a lot of portraits of individuals. Everyone had a different sign and hat and cause and voice. Looking at the pictures did not capture the collective effervescence that we all felt. There were even people crying on the streets watching the seas of people.

I decided that in order to make a portrait of the collective it had to be a collection of the individuals.

I tried to reproduce that effervescence that I felt by creating a video with music and poetry to recreate the elevation beyond the individual experience.

Here is that video (please put the video in HD to get the full effect).

I particularly like the way that the article is constructed. I like that everyone draws on their personal experience of Women’s March and provided different but interrelating themes and perspectives and felt deeply moved.

It is interesting to see what constitutes our modern day collective effervescence, our modern totemism. The collective formed by those who was participating in Women’s March uphold the same progressive beliefs, similar as the religious beliefs. And as Henry points out, the pink pussy hat is designated as the totem for this °temporary° collective of participants in the march. Each specific cause, as Clara mentions, serves as the individual totemism, or sub-totem of a smaller group. Together, they all contribute to the reproduction of the collective who has faith in woman rights.

This is a very vivid account of what was truly happening during collective effervescence and how the society gives individuals moral uplift and higher meaning in mundane life.

LikeLike

One of the many criticisms of the women’s march was that there were many different issues being promoted or protested, and the entire event seemed disjointed and unfocused. While I think there were a lot of very legitimate problems with the women’s marches, I don’t think that this was one of them. I liked the way it was put in this article, that “Though our individual causes varied, protesters agreed that 1) we need to address many problems, and 2) we can only solve these problems collectively.” ‘Women’s Rights’ means a lot of things, and advocating for equality doesn’t mean simply winning the right to vote and then patting ourselves on the back for a job well done. Oppression is complicated and extensive and goes way beyond the right to civically engage. Achieving equality means working towards environmental justice and fighting against global warming, because poor rural women in developing nations will be the ones who will feel the effects most acutely. It also means fighting for the rights of women to practice whatever beliefs they wish, to wear whatever they wish without fear of harassment, abuse, the possibility of losing their jobs or social standing, or of not being taken seriously in the workforce or academia. It means proper, accessible reproductive care for all women, including women of color, women living below the poverty line, and trans women. It means equal right to education and career opportunities and many, many other issues. They are all related and, as mentioned above, cannot be solved unless we form an inclusive collective to fight for these rights. The women’s march had lots of problems, and too often it fell short when it came to true intersectionality. I’ve heard it described as the cis-white-women’s march, and I think that there is some truth to the statement. But the number of different signs and chants and issues I saw being promoted that day made me feel better about the march. I thought that perhaps people might see that when they speak about “women’s issues”, they’re speaking about all these issues and more, and they’re speaking about all women.

I think that the use of totems could be extremely useful in the creation of such a collective. The pussyhats were a step in the right direction, but as effective as they were in bringing marchers together and adding to the collective effervescence, they also seemed at times to be alienating to transgender women. I think that the community of women is in need of a totem to remind them that they are indeed all part of the same collective, and one woman’s oppression harms all of us.

LikeLike

This blog post was a great examination of the relationship between the collective and the individual self. Durkheim emphasizes that the human self has a collective component; our souls represent our feelings of the collective within us. You three demonstrated this collective basis for the self in your description of the moral uplift you all felt at the Women’s March. You all describe this sense of empowerment and feeling of being a part of something greater than yourselves. It is interesting to connect this uplift with your Durkheimian soul; the beliefs expressed by the people around you resonated with the collective representations within you. You make the good point that the beliefs being championed–namely support for equal rights and representation–were iterated in many different causes, such as immigrant rights, climate change activism, etc, but they were based in the same collective representations that are internalized in the members of American society. Hearing about the sense of unity you all felt at the march got me wondering how members of American society can form such different beliefs based on shared group experiences. This brings in Durkheim’s explanation of the duality of man–the individual representations in all of us also contribute to our selves and to differing interpretations of the same social.

LikeLike

When reading Durkheim, one may have trouble relating the corroboree to our time. It seems foreign, mystical, and tribal, so one may not believe that the corroboree and its effects have any relation to current society. Although Durkheim claims to be studying the ahistorical nature of human beings, the reader may be skeptical of his theories’ applicability. I thought that this blog post clearly demonstrated that Durkheim’s theories are applicable to our society, specifically in that it gave personal accounts of the feeling of collective effervescence – this blog post was not simply drawing parallels between the corroboree and modern day events, which made Durkheim’s claims feel even more tangible. Moreover, although each of the three accounts of the march was unique, they all possessed similar themes and came to similar conclusions, emphasizing the true collective nature of the march and of the unifying experience of the modern corroboree.

LikeLike

I think that there is an interesting point that was touched on, about why Donald Trump isn’t part of the collective, and a threat to it. If he is a threat to our collective then why was he elected in the first place? We talked in class about the divide in America where the collectives focus more on our political beliefs rather than the collective being America. The question where does that put the future of our country if we are splitting our collective and subscribing to new/different ideas about the world and others in it. Durkheim says that this is the break down of society, will that be true for us?

LikeLike

This post was really fascinating! I really liked the way you drew in personal real world experiences of the Women’s March, which I think in and of itself is a really strong example of that feeling of collective effervescence we feel in group activities like this, at least as Durkheim describes. Maybe rather than feeling as though we’re being controlled by something else, we instead feel like we’re part of something greater. I think that the symbolism of the hats, the collective issues that we must come together to attempt to solve are all good instantiations of Durkheim’s theories. I really personally like how you talked about how the numerous different “causes” were in some way strongly unified and based in the same goals and how your experience as part of the collective allowed you to feel like all of these issues being brought up were still in some way something that everyone supported as part of this collective regardless of whether it seemed to directly affect or apply to them. Overall, this was a super interesting and thought-provoking post!

LikeLike